Supporting and Evaluating Professional Collaboration Among Secondary Mathematics and Science Teachers

Data analysis resulted in the emergence of three central categories of Process

Behaviors generalizing the discipline-specific frameworks for STEM inquiry and three

categories of Dispositional Behaviors related to their discourse. A central

construct of Decentering also emerged for following facilitator moves to manage

the discourse. Four categories of Teacher Beliefs that influenced their ability

or willingness to change teaching practices emerged.

Process Behaviors.

Process behaviors focus on the interactions within a PLC to resolve identify and

resolve problems related to STEM content, instruction, student thinking, etc. Generalizing

the three discipline-specific frameworks helped us identify and understand instances of

similar behaviors and interactions across the STEM disciplines. We subsequently drew on

John Dewey's constructs of inquiry and emergence in cognitive tool use (Dewey, 1910;

Hickman, 1990) as we identified and characterized three central categories of behaviors

related to scientific inquiry:

- productive engagement (e.g., members engage in exploring a common problematic issue, clarify the nature of the problem, and encourage participation of all members),

- conceptual resources(e.g., members are intentional in their selection of conceptual resources to apply to a problem, apply appropriate and powerful ideas, and seek appropriate external assistance when there is a gap in their collective understanding), and

- persistence and reflection (e.g., members stay engaged until a problem is resolved, evaluate the quality of their solution, and reflect on the effectiveness of the tools they applied).

"That

doesn't make sense": How taking an inquiry stance affects group interaction and conceptual

understanding

To illustrate the role of process behaviors, we will present a

video case of one PLC whose typical interaction was not productive in terms of

developing conceptual reasoning or effective STEM behaviors. However, there were some

notable exceptions, sometimes as a result of a particular activity or intervention by the

instructor, but also emerging from the group. The dominant mode of interaction for this

group was driven by two participants. One of these participants consistently attempted to

make connections between various representations leading regularly to him pointing out

contradictions in the group's work. He was typically not able to engage the remainder of

the group in addressing these problems. The second dominant participant regularly tried to

explain away these contradictions often not fully understanding the issue and offering

illogical resolutions. We found the more productive episodes were characterized by

radically different process behaviors.

Dispositional Behaviors. Each of the discipline-specific frameworks include attributes of the individual such as affective qualities and metacognitive skills. We built on observable aspects of these attributes to identify and characterize dispositional behaviors which converged around three central categories:

- conceptual orientation (e.g., members clarify ideas, focus on meanings in mathematical and scientific activity, and identify and resolve ambiguity),

- intellectual integrity (e.g., members provide rationale for claims, exhibit honesty about lack of understanding, and show willingness to challenge others and be challenged), and

- coherence (e.g., members seek connections among ideas and topics, express ideas using multiple representations, and generalize conclusions or find limiting conditions).

From deference to promoting intellectual integrity: Understanding a

trajectory of teacher collaboration

To illustrate the role of dispositional

behaviors, we will present the trajectory of a group of four high school math and science

teachers during the first semester of the Project Pathways sequence. We discuss the

changes (or lack thereof) of the group members and argue that they are best understood in

the context of the evolution of the entire group's dynamics. Most compelling was the range

in variation in the changes of STEM Behaviors across the teachers in this group. For

example, one of the teachers made significant improvements over the semester related to

his covariational reasoning and in the way he interacted with the others in his group. On

the one hand, this change was enabled by specific dynamics of the group such as the

eagerness of others for his help and their willingness to indicate to him when they did

not understand. Reciprocally, this teachers' reactions encouraged more of this sort of

openness, modeled productive dispositional behaviors, and positively influenced others'

opportunities to learn. However, for the second teacher, we saw very little change in

covariational reasoning and only superficial changes in the nature of his interaction.

While his content knowledge was particularly strong as measured by our assessment

instruments, his calculational orientation and lack of attention to others' understanding

constrained his peers' willingness to engage and their opportunities to learn. This style

of interaction was reinforced, however, by other teachers' compliance in receiving answers

they did not understand. Thus the group reacted in seemingly contradictory manners in

response to these two teachers, actively encouraging conceptual dialog over calculational

dialog with the first teacher described above but encouraging the opposite from the other

teacher. We resolve this in terms of the interaction within the whole system and by

accounting for different aspects of the classroom tasks or of the group communication

being taken as problematic by different teachers at different times.

Beliefs and

Attitudes. The project documented shifts in teachers' views about the methods and

nature of mathematics and science using several survey instruments and analysis of

interview and PLC data. Coding of these beliefs converged around four categories:

- factors of resistance related to perceived barriers such as the need for coverage or support of administrators;

- beliefs about STEM learning such as what constitutes understanding or whether unsuccessful attempts at a problem indicate weakness,

- beliefs about STEM teaching such as the purposes of assessment or whether it is important to understand student thinking; and

- perceived ability in STEM disciplines and teaching including feelings of preparedness and confidence in their understanding of how central ideas of their courses develop in students.

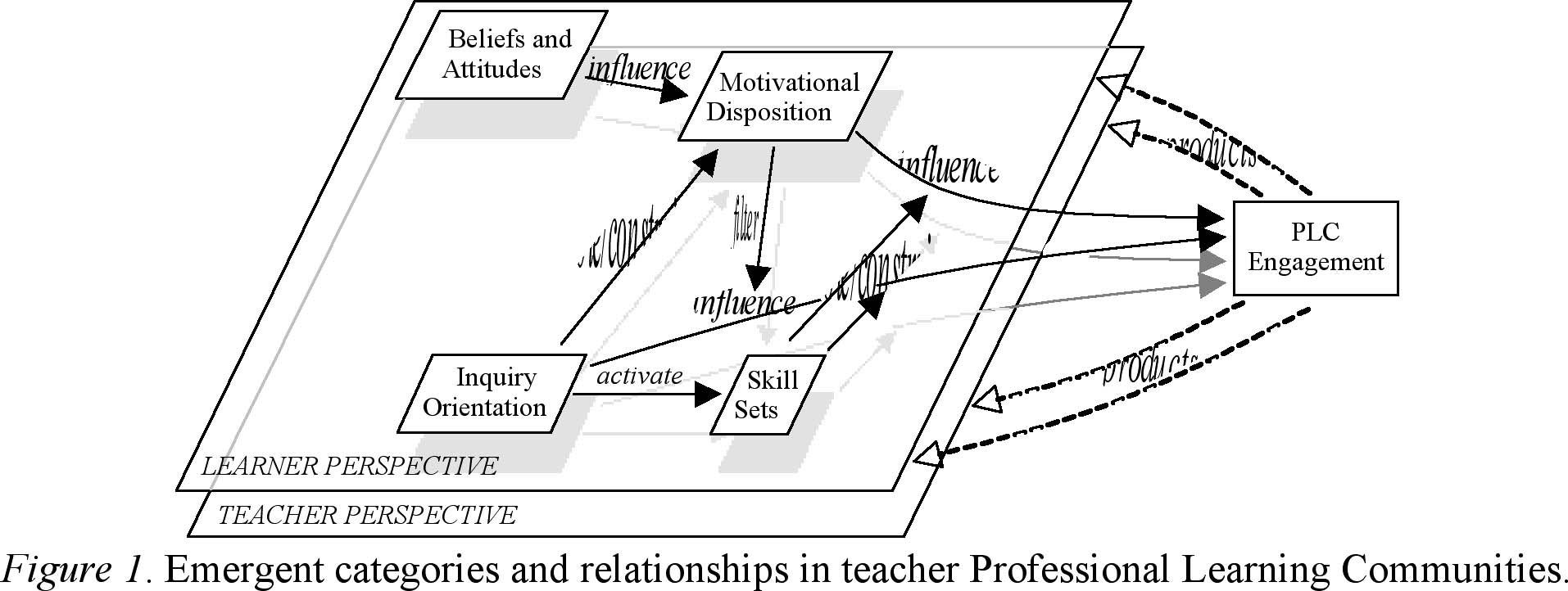

The Interplay

between Process Behaviors, Dispositional Behaviors and Beliefs. We found that project

teachers primarily interacted from two different perspectives, illustrated as parallel

planes in Figure 1. From a "teacher perspective," they focused on issues about students'

thinking and learning or clarifying content to a colleague. From a "learner perspective,"

they wrestled with understanding the content themselves. While teachers often switched

between these perspectives, we never observed an individual actively participating from

both at the same time. Although, the perspectives parallel one another in the sense of

containing the same relationships between attributes and consisting of similar language

and tools, we observed that effective communication required participants to either take

the same perspective or for some to be teaching directly to the active learning issue of

the other teachers.

Decentering and Facilitator Strategies. Tracking the

facilitation abilities of PLC facilitators revealed interaction patterns between the

facilitator and other PLC members that influenced the quality of inquiry among the group.

Our analyses also revealed that to actively facilitate teachers in a PLC requires that the

facilitator "place" her or himself in the other members' shoes. "Placing oneself in

another's shoes" is a classic instance of what Piaget (1955) identified as

decentering, or the attempt to adopt a perspective that is not one's own. Steffe

and Thompson (2000) extended Piaget's idea of decentering to the case of interactions

between teacher and student (or mentor and protege) by distinguishing between ways in

which one person attempts to systematically influence another. Analysis of the

facilitators revealed five manifestations of decentering, ranging from the facilitator

showing no interest in understanding the thinking or perspective of other PLC members to

the facilitator building a model of other members' thinking, respecting their internal

rationality, and adjusting her/his actions to account for these perspectives.